Why “Eat Real Food” Isn’t a Nutrition Strategy

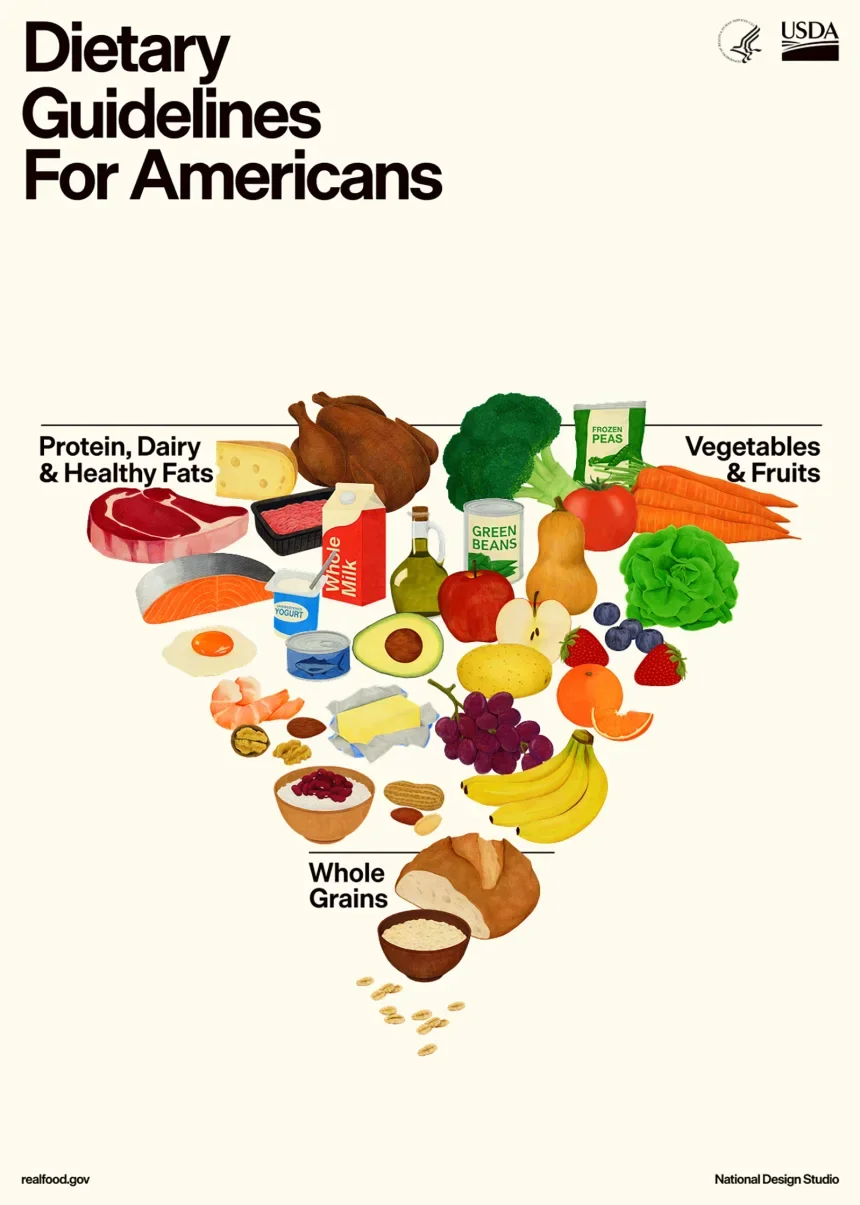

The latest update to the Dietary Guidelines includes this image of an inverted pyramid. (HHS/USDA)

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030, just dropped—and, to put it mildly, they’re polarizing. On the surface, their message seems simple: “eat real food.” But in practice? It’s anything but.

Reading through the guidelines made me pause and reflect on the widening gap between the nation’s wealthiest and the nation’s poorest households. So much health and nutrition advice is geared towards those with money, access, and flexibility—while those without continue to fall through the cracks.

What’s most frustrating is the sense that the people writing these guidelines don’t fully understand who they’re actually writing them for. The result? Recommendations that feel aspirational, idealistic, and, for many Americans, completely unachievable.

Make America Healthy Again

The language of the guidelines is bold and well-intentioned—but it reveals a deeper disconnect.

“To make America Healthy Again, we must return to the basics. American households must prioritize diets built on whole, nutrient-dense foods—protein, dairy, vegetables, fruits, healthy fats, and whole grains. Paired with a dramatic reduction in highly processed foods laden with refined carbohydrates, added sugars, excess sodium, unhealthy fats, and chemical additives, this approach can change the health trajectory for so many Americans.”

I almost shudder typing these words, because they feel completely out of touch with the realities many people face. Wouldn’t it be lovely if everyone could easily access a grocery store within five miles of their home, reliably drive there, and afford nutrient-dense foods instead of highly processed, shelf-stable options that feed larger families, last longer, and stretch tighter budgets?

As a dietitian, I know the science: nutrient-dense foods are associated with better health outcomes than ultra-processed foods. But who does this advice actually apply to?

The single mom working two jobs who can’t afford an apartment with a stove or refrigerator and ends up feeding her kids McDonald’s for dinner instead of a head of broccoli?

The college student juggling tuition, rent, and a part-time job, surviving on ramen, frozen meals, and granola bars because fresh produce and protein are expensive, perishable, and unrealistic for their schedule?

This isn’t about ignorance or laziness. It’s about a system that sets many Americans up for failure before they even step foot in a grocery store.

The General Gist

At first glance, the guidelines largely echo what previous versions have promoted and what most nutrition professionals already practice. Before diving into my perspective, here’s a quick recap of the core recommendations:

Eat the right amount for you.

Prioritize protein foods at every meal.

Consume dairy.

Eat vegetables and fruits throughout the day.

Incorporate healthy fats.

Focus on whole grains.

Limit highly processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates.

Limit alcoholic beverages.

On paper, these recommendations make sense. But they also assume consistent food access, transportation, storage space, cooking equipment, time, and disposable income—assumptions that don’t reflect how many Americans actually live.

That’s where the gap between aspiration and reality becomes glaring.

A Dietitian’s Take on Each Recommendation

Eat the right amount for you: In theory, yes—“the calories you need depend on your age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity.” But portion guidance only works if people have enough food and the kitchen tools to measure or control servings. For many households, this is simply not the case.

Prioritize protein foods at every meal: Protein is having its continued moment, and it plays an important role in satiety and muscle health. However, fresh protein sources can be costly, difficult to store, or inconvenient for busy families. Notably, the updated guidelines represent a significant shift by increasing protein emphasis—encouraging protein at every meal rather than as part of an overall balanced diet. While protein needs are highly individualized, this change raises important questions about feasibility, affordability, and flexibility.

Consume dairy: The guidelines recommend including full-fat dairy with no added sugars. Dairy does provide important nutrients, but the evidence on full-fat dairy and cardiovascular health is mixed and highly dependent on overall dietary pattern and individual risk. Nuance is essential here—especially for populations already at higher risk for heart disease.

Eat vegetables and fruits throughout the day: This is ideal in theory, but availability, shelf life, and price often make it aspirational rather than actionable. Frozen and canned options can help bridge this gap, and while the guidelines briefly acknowledge this, it deserves far greater emphasis.

Incorporate healthy fats: The guidelines specifically suggest cooking with butter or beef tallow, which research has linked to heart disease. Healthy fats from nuts, seeds, oils, and avocado are excellent alternatives—but can be expensive and perishable for families on tight budgets.

Focus on whole grains: Again, this recommendation is sound—but shelf-stable refined grains are often cheaper, more convenient, and more accessible than whole-grain alternatives.

Limit highly processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates: Sounds great in theory, yet ultra-processed foods are frequently the most affordable and convenient option for busy families trying to feed themselves and their children reliably.

Limit alcoholic beverages: The guidance encourages consuming less alcohol for better health. Alcohol is a known carcinogen, and no amount is truly risk-free. Yet moderation is often framed around social connection—a consideration rarely extended to foods like pasta or dessert in social settings. This inconsistency highlights the challenge of creating guidelines that are both evidence-based and culturally realistic.

It’s Not a Knowledge Gap—It’s an Access Gap

I work with people across the socioeconomic spectrum. I work with clients who are food insecure and regularly run out of food before they have money to buy more. I also work with clients who are wealthy and can afford to pay out of pocket for nutrition counseling.

And the most common things I hear from both groups?

“I know I need to eat more fruits and vegetables.”

“I try to prioritize protein, but it’s hard to fit it in at every meal.”

The American people aren’t stupid when it comes to nutrition. They know what supports better health. But the system we’ve built doesn’t allow many of them to act on that knowledge.

So let’s stop telling people to “eat real food” without building the systems that allow real people to actually access it.

Why “Just Eat Better” Has Never Worked—and Never Will

If the goal of the Dietary Guidelines is truly to improve public health, then the conversation has to move beyond individual willpower and idealized food choices. Guidelines without access are just aspirations, not solutions. Until we invest in food access, affordability, education, and structural support, telling Americans to “eat real food” will continue to miss the mark. Health isn’t just about knowing what to eat—it’s about having the ability to do it.