The Updated Dietary Guidelines, in a Nutshell

HHS/USDA

Before this most recent release of the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines For Americans, I’d guess that most Americans had no idea a formal set of guidelines for how we should eat even existed. And honestly? It’s not especially important for that they do. Generally speaking, these guidelines aren’t written for everyday decision-making at the grocery store or dinner table—they’re primarily meant to inform food and nutrition policy, like what can be purchased with government assistance dollars or what foods are served in schools and other institutions.

That said, every few years the guidelines are updated, and every few years there’s a predictable wave of headlines telling us to panic, overhaul our kitchens, or suddenly eat like a completely different person. Typically, that uproar stays mostly within the nutrition and public health world. But this most recent update seems to have sparked interest well beyond the professional bubble, pulling in people who don’t spend their days thinking about nutrition policy—and that’s what makes this moment a little different.

So let’s talk about what actually changed—and what didn’t.

“Eat real food”

If there’s one phrase from the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans that’s sparked far more buzz than usual, it’s this: “eat real food.” Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was a driving force behind these guidelines, and that signature message—simple as it sounds—captures the spirit of what the committee is aiming for.

But “eat real food” isn’t a marketing tagline—it’s a guiding principle that underpins eight broader recommendations meant to shape eating patters in ways that support long-term health. Here’s what they are, in a nutshell:

Eat the right amount for you.

Prioritize protein foods at every meal.

Consume dairy.

Eat vegetables and fruits throughout the day.

Incorporate healthy fats.

Focus on whole grains.

Limit highly processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates.

Limit alcoholic beverages.

On paper, these recommendations sound great. And after digging into the updated guidelines, it’s clear they lean heavily into protein, healthy fats, and minimally processed foods.

And yes—science supports this. Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and quality protein sources are consistently associated with better health outcomes. But here’s the catch: for many Americans, eating “real food” isn’t actually accessible. Food deserts, limited budgets, long work hours, and time constraints make a perfectly balanced, minimally processed diet more aspirational than achievable. The guidelines may be well-intentioned, but they don’t always reflect the realities most people are navigating day to day.

What stands out to me, as a dietitian

Fiber is encouraged, but without clear targets. The guidelines say to “eat more fiber,” but don’t include specific goals (about 25 grams/day for women and 38 grams/day for men). With limited emphasis on whole grains and no clear spotlight on beans or legumes, meeting fiber needs may be challenging.

There’s a heavy emphasis on red meat and full-fat dairy, which raises some concerns. These foods are high in saturated fat, which is consistently linked to increased cardiovascular risk. While the research on saturated fat is mixed, it’s important to be considerate of this.

Alcohol guidance is vague. Previous guidelines included clear limits (up to 1 drink/day for women and up to 2 drinks/day for men). Removing specific guidance may leave people unaware of how to reduce alcohol-related health risks.

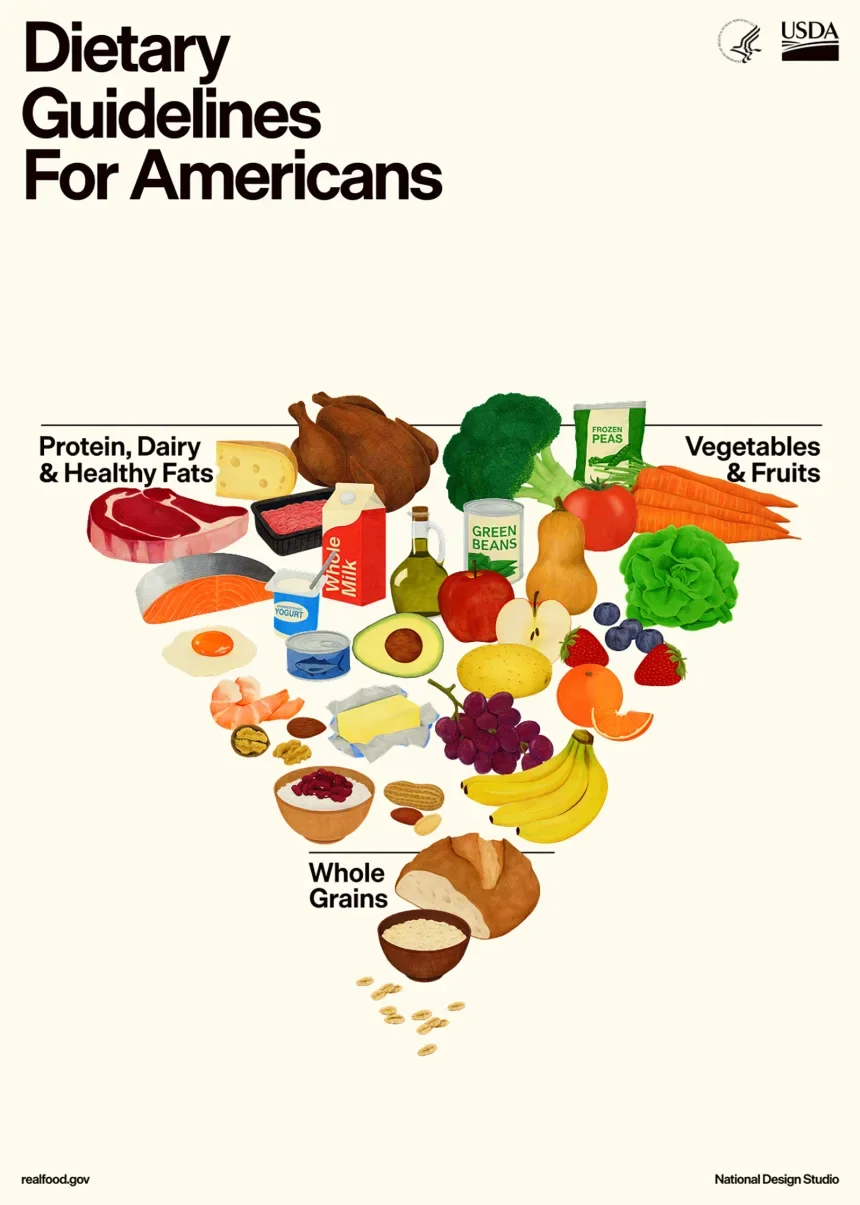

Moving away from MyPlate feels like a cause for confusion. These guidelines critique older food models, like the food pyramid, only to reintroduce a pyramid-style framework, while moving away from MyPlate. MyPlate was great to use in practice because it helped people visualize balanced meals. The new upside-down pyramid makes it difficult to understand why should and should not be prioritized.

In my opinion, dietary guidance should be clearer, more actionable, and better aligned with the strongest evidence for long-term health.

And then there’s the question of bias

Another layer worth acknowledging is that the research informing these guidelines is not entirely neutral. Much of it is funded or influenced by industries with vested interests—dairy, meat, grains, and more. That doesn’t mean the science should be dismissed outright, but it does mean it deserves a critical eye. This is especially important when recommendations shift dramatically, like protein intake increasing by 50–100%, which is no small change.

Where this falls apart in practice

One of the reasons tools like MyPlate were so effective is that they were visual and intuitive. You didn’t need to read a report or interpret an abstract—you could look at a plate and understand how foods might fit together in real life. The updated guidelines move away from that simplicity, introducing an upside-down pyramid that’s far less intuitive and much harder to translate into an actual meal.

For something meant to guide eating patterns, it misses the mark on usability.

So what does this mean for you?

In theory—not much. Your daily habits don’t need to change overnight because of a new pyramid or a new headline. “Eat real food” is solid advice, but advice only works when it’s practical, affordable, and culturally relevant. For most people, the best approach remains the same: focus on balance, consistency, and flexibility—within the constraints of real life.

Because the most nourishing way to eat isn’t the one that looks best on paper—it’s the one you can actually sustain.